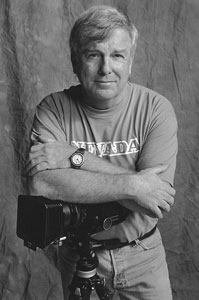

Price native/Alumnus Richard Menzies displays work in Gallery East

Price native Richard Menzies remembers clearly the day his life changed forever over half a century ago.

“Actually it was nighttime. Eddie Conover and I had just emerged from the Price Theater. Next door to the movie house was Barney’s Photo Shop, and in the window of the shop was a Kodak Brownie Holiday Flash Outfit. Also on display was a sign: easy terms. The following day I peddled my bike downtown and asked the proprietor, Barney DiVietti, if he would give me easy terms on that $10 Kodak.

This archived article was written by: press release

Price native Richard Menzies remembers clearly the day his life changed forever over half a century ago.

“Actually it was nighttime. Eddie Conover and I had just emerged from the Price Theater. Next door to the movie house was Barney’s Photo Shop, and in the window of the shop was a Kodak Brownie Holiday Flash Outfit. Also on display was a sign: easy terms. The following day I peddled my bike downtown and asked the proprietor, Barney DiVietti, if he would give me easy terms on that $10 Kodak.

“Without batting an eye, Barney agreed,” Richard recalls. “I handed him a fistful of $2 and he handed me the camera. Four months and four payments later, it was mine. Barney didn’t charge interest, but he had a way of kindling mine.”

Menzies credits DiVietti for getting him started on a hobby that would grow into a lifelong passion. Other mentors included Jim Stagg, William Fossat and Fred Babcock – who had a key to the college chemistry building and used to sneak him into the college’s darkroom.

“I’d stay up all night long, developing film and making prints. Come dawn, I’d let myself out a back window and run home with an armload of wet pictures. My fingers were brown and I reeked of sodium thiosulfate.

Richard had a dream: to win a prize in the weekly Summertime Snapshot Contest, sponsored jointly by Eastman Kodak and the Salt Lake Tribune. In all, he ended up winning the contest 38 times, including an International Third Place in 1970. The $2,500 prize enabled him to buy a better camera and turn professional. In the years since, he worked in portrait studios and commercial labs and as a newspaper and television correspondent – until finding his niche as a freelance magazine journalist.

“I’ve always preferred to work alone with a minimum of supervision,” he says. “Downside of freelancing is that you have nothing in the way of financial security. Upside is that you are free to go your own way and – best of all – you retain the copyrights to your work.”

By way of illustration, Menzies points to a photograph of New Zealand motorcycling legend Burt Munro, which he shot in 1971 – decades before Munro became a legend, thanks to the film The World’s Fastest Indian. Since that movie came out in 2005, he estimates he’s sold the picture almost four thousand times, to publications and racing enthusiasts around the world.

Also in 2005, Stephens Press published Menzies’ first book, Passing Through, which profiles in pictures and words a number of eccentrics and impossible dreamers in the mold of Burt Munro. Such people as Melvin Dummar, who claims to have picked up billionaire Howard Hughes in the Nevada desert. And Frank Van Zant, who renamed himself Chief Rolling Mountain Thunder and proceeded to build a rococo roadside monument out of concrete and junk – at the urging of The Great Spirit. And Stanley Gurcze, a double-amputee hitchhiker who spent a lifetime hitching the highways in search of “an honest man.”

More recently, Richard and his vintage 1973 Volkswagen bus were featured in an hour-long PBS documentary: The Big Empty.

“Seeing my face in high-definition,” he says, “I realize that I have come to resemble those weather-beaten desert rats who have long been my stock in trade.”

In the Darkroom

“Thanks to the digital revolution,” Menzies says, “photography has undergone its first major transformation since the days of Matthew Brady. No longer is it necessary to know one’s way around a darkroom in order to make pictures. No longer does the process involve film, chemicals, photographic paper, safelights and such. You can now upload and download, manipulate and print photos on a computer, in broad daylight!”

But, for all its advantages, Menzies still employs the old time-tested methods of photography. “Say what you will in praise of digital, and indeed there is much to be said that is praiseworthy” he says. “It’s a wonderful tool and a giant leap forward. However, when it comes to black and white, I still prefer the silver-gelatin process. Why? Because instead of printing with ink, I’m painting with light. I’m waving my dodging wand above the easel like a symphony conductor, I’m plunging my hands into the soup. I’m doing everything I can think of to draw out the middle tones, deepen the darks and clarify the highlights. Try as I might, no two prints turn out exactly the same – just as no two musical performances are the same. Because music – real music – comes not from a machine but from a human being.”

Beginning Sept. 28-Nov. 6, an exhibit titled Passing Through: Photographs by Richard Menzies, will be displayed at CEU’s Gallery East. On Oct. 2 from 7- 9 p.m., the artist will gallery goers and sign copies of his award-winning book. Students, faculty and members of the community are invited to attend.

Gallery East is open Monday through Thursday from 11:00 to 5:00 P.M. The gallery is closed Fridays, weekends, and holidays. The exhibit is free and open to the public. For more information, contact the gallery at: 435-613-5327; or contact Noel Carmack at: 435-613-5241 or [email protected]